Penelope Boston studies caves and karst formations, and the special biology that lives in them — both here on Earth and possibly on other planets.

Why you should listen

Penelope Boston is fascinated by caves — secret, mineral environments that shelter mysteries in beguiling darkness and stillness. She’s spent most of her career studying caves and karst formations (karst is a formation where a bedrock, such as limestone, is eaten away by water to form underground voids), and is the cofounder of the new National Cave and Karst Research Institute, based in New Mexico.

Deep inside caves, there’s a biology that is like no other on Earth, protected from surface stress and dependent on cave conditions for its survival. As part of her work with caves, Boston studies this life — and has made the very sensible suggestion that, if odd forms of life lie quietly undiscovered in Earth’s caves, there’s a good chance it might also have arisen in caves and karst on other planets. Now, she’s working on some new ways to look for it

The career that I started early on in my life was looking for exotic life forms in exotic places, and at that time I was working in the Antarctic and the Arctic, and high deserts and low deserts. Until about a dozen years ago, when I was really captured by caves, and I really re-focused most of my research in that direction.

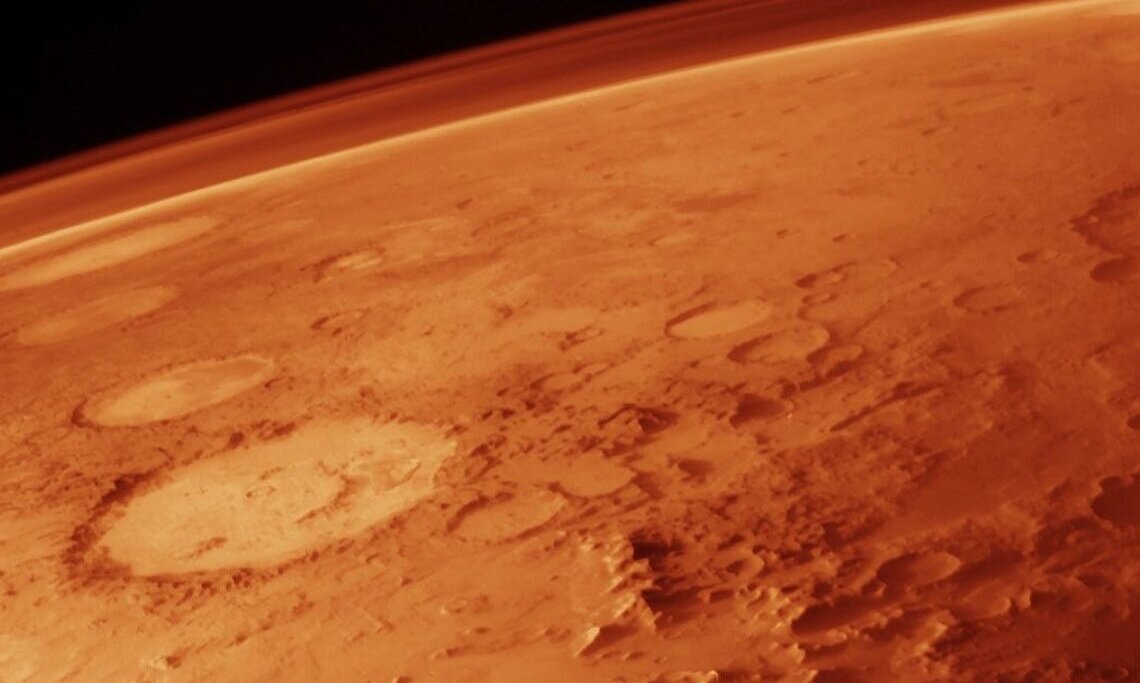

So I have a really cool day job– I get to do some really amazing stuff. I work in some of the most extreme cave environments on the planet. Many of them are trying to kill us from the minute we go into them, but nevertheless, they’re absolutely gripping, and contain unbelievable biological wonders that are very, very different from those that we have on the planet. Apart from the intrinsic value of the biology and mineralogy and geo-microbiology that we do there, we’re also using these as templates for figuring out how to go look for life on other planets. Particularly Mars, but also Europa, the small, icy moon around Jupiter. And perhaps, someday, far beyond our solar system itself.

I’m very passionately interested in the human future, on the Moon and Mars particularly, and elsewhere in the solar system. I think it’s time that we transitioned to a solar system-going civilization and species. And, as an outgrowth of all of this then, I wonder about whether we can, and whether we even should, think about transporting Earth-type life to other planets. Notably Mars, as a first example.

Something I never talk about in scientific meetings is how I actually got to this state and why I do the work that I do. Why don’t I have a normal job, a sensible job? And then of course, I blame the Soviet Union. Because in the mid-1950s, when I was a tiny child, they had the audacity to launch a very primitive little satellite called Sputnik, which sent the Western world into a hysterical tailspin. And a tremendous amount of money went into the funding of science and mathematics skills for kids. And I’m a product of that generation, like so many other of my peers. It really caught hold of us, and caught fire, and it would be lovely if we could reproduce that again now.

Of course, refusing to grow up — — even though I impersonate a grown-up in daily life, but I do a fairly good job of that — but really retaining that childlike quality of not caring what other people think about what you’re interested in, is really critical. The next element is the fact that I have applied a value judgment and my value judgment is that the presence of life is better than no life. And so, life is more valuable than no life. And so I think that that holds together a great deal of the work that people in this audience approach.

I’m very interested in Mars, of course, and that was a product of my being a young undergraduate when the Viking Landers landed on Mars. And that took what had been a tiny little astronomical object in the sky, that you would see as a dot, and turned it completely into a landscape, as that very first primitive picture came rastering across the screen. And when it became a landscape, it also became a destination, and altered, really, the course of my life.

In my graduate years I worked with my colleague and mentor and friend, Steve Schneider, at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, working on global change issues. We’ve written a number of things on the role of Gaia hypothesis — whether or not you could consider Earth as a single entity in any meaningful scientific sense, and then, as an outgrowth of that, I worked on the environmental consequences of nuclear war.

So, wonderful things and grim things. But what it taught me was to look at Earth as a planet with external eyes, not just as our home. And that is a wonderful stepping away in perspective, to try to then think about the way our planet behaves, as a planet, and with the life that’s on it. And all of this seems to me to be a salient point in history. We’re getting ready to begin to go through the process of leaving our planet of origin and out into the wider solar system and beyond.

So, back to Mars. How hard is it going to be to find life on Mars? Well, sometimes it’s really very hard for us to find each other, even on this planet. So, finding life on another planet is a non-trivial occupation and we spend a lot of time trying to think about that. Whether or not you think it’s likely to be successful sort of depends on what you think about the chances of life in the universe. I think, myself, that life is a natural outgrowth of the increasing complexification of matter over time.

So, you start with the Big Bang and you get hydrogen, and then you get helium, and then you get more complicated stuff, and you get planets forming — and life is a common, planetary-based phenomenon, in my view. Certainly, in the last 15 years, we’ve seen increasing numbers of planets outside of our solar system being confirmed, and just last month, a couple of weeks ago, a planet in the size-class of Earth has actually been found. And so this is very exciting news.

So, my first bold prediction is that, is that in the universe, life is going to be everywhere. It’s going to be everywhere we look — where there are planetary systems that can possibly support it. And those planetary systems are going to be very common. So, what about life on Mars? Well, if somebody had asked me about a dozen years ago what I thought the chances of life on Mars would be, I would’ve probably said, a couple of percent. And even that was considered outrageous at the time. I was once sneeringly introduced by a former NASA official, as the only person on the planet who still thought there was life on Mars. Of course, that official is now dead, and I’m not, so there’s a certain amount of glory in outliving your adversaries.