Vaccine Priority Groups

Principles guiding the prioritisation of the vaccine include scientific evidence, ethics and deliverability. Science should provide the evidence and data on risk of COVID-19 severe morbidity and mortality for different population groups, which underpins prioritisation decisions. From an ethical perspective, prioritisation should maximise benefit and reduce harm, be fair and transparent, and address health inequalities. Finally, deliverability should be considered in formulating the prioritisation such that the approach is simple to communicate to the public and professionals and realistic to implement.

This conceptual framework and its application to key population groups that have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 is discussed below and summarised in table 1.

Proposed prioritisation

The decision to prioritise one population group over another to have early access to the vaccine is not an easy or straightforward one and should take into account scientific evidence, ethics and deliverability (implementation). Based on preliminary information on the vaccines in development, JCVI agreed that a programme that combines clinical risk stratification, an age-based approach and prioritisation of health and social care workers should optimise both outcomes and deliverability (see reference 1). Simple age-based programmes are usually easier to deliver and therefore achieve higher uptake including in the highest risk groups. Table 1 summarises the scientific rationale, ethical considerations for maximising benefits and reducing health inequalities, and deliverability for each of these population groups.

Scientific Evidence

Prioritisation of people in older age groups and with clinical risk factors is based on the current evidence that strongly indicates that the absolute risk of serious disease and death increases exponentially with age (see reference 3). Mortality is also higher in those with underlying health conditions, although this is also very strongly related to age with low absolute risks in those under 40 years of age (see reference 4).Frontline health and social care workers are at increased risk of exposure, increased risk of transmitting the infection to vulnerable patients, and their health is key to maintain resilience in the NHS and for health and social care providers.

However, other population groups might also be considered for prioritisation of the vaccine. While the evidence indicates that age has the highest absolute risk, studies have also shown that there are several factors which include inequality domains and protected characteristics that are associated with elevated incidence or adjusted risk ratios, such as male sex, black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups, people with multiple comorbidities and deprivation (see references 5 and 6). Indeed, in the OpenSafely risk prediction model, an Asian or a black person reaches the equivalent age-risk of COVID-19 of a white 65 year old at 60 years without co-morbidities and at 45 years or 43 years, respectively, if they have two co-morbidities (see reference 7). If split by sex this equivalent age is lower in men compared to women. So, the question could be posed: should men or people belonging to BAME groups also be prioritised?

The male female differences in COVID-19 mortality are not straightforward, with likely interaction of age and sex along with other factors that have a sex differential:

- co-morbidities

- occupation

- behavioural factors (including smoking and alcohol use)

- compliance with social distancing measures

- shielding.

The explanation for sex differences may reflect social and cultural factors related to gender rather than the biology of sex (see reference 8). Additionally, focusing on men’s higher death rates compared to women may be misleading since the absolute differences will be higher, despite similar relative risk, given men’s higher baseline mortality (see reference 9). It is also important to note that, while risk increases with age for both men and women, the age cut off at 50 years is below the age at which absolute risk starts increasing for women (see reference 7), therefore capturing everyone at increased risk.

We know that people of BAME groups also tend to have a higher relative risk of having the infection and complications from the disease when compared to their counterparts of White ethnic groups (see reference 6). The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) ethnicity sub-group recently prepared a paper on the drivers of the higher COVID-19 incidence, morbidity and mortality among minority ethnic groups which concluded that, based on the available evidence at the time, “the relative importance of different pathways that cause ethnic inequalities in COVID-19 is not well understood” (see reference 10).

Importantly, the authors also point out that they are highly confident that social factors (such as poverty and occupation) make a large contribution to the greater burden of COVID-19 in ethnic minorities; that they have medium confidence that some clinical conditions, which are associated with severe COVID-19 are more common in some ethnic minority groups, may contribute to the ethnic inequalities seen; and that they are highly confident that genetics alone cannot explain the higher burden of COVID-19 of people in some ethnic groups over others.

It is important to note that the data have significant limitations. While OpenSafely has a sample of 17 million people on GP systems, these systems do not include unregistered people (who may belong to underserved groups), ethnicity is not optimally recorded, and they cannot measure some fundamental confounders, such ability to adhere to social distancing measures, shielding, social interactions, occupation, and unknown residual confounders. Furthermore, much of the data that is being used now was obtained in the early part of the pandemic, which presents particular limitations.

Ethics

From an ethical perspective, prioritisation should:

Maximise benefit and reduce harm

Scientific evidence, like the one outlined above, allows us to focus on populations that are at highest risk of infection, hospitalisation, and death from COVID-19. It is important that these population groups are the first to receive the vaccine, as they are the most likely to benefit from them.

But this principle is not just about individual benefit. Maximising benefit and reducing harm is also about protecting some population groups in order to reduce transmission to those at highest individual risk and about maintaining health system resilience. Health and social care workers may not take much personal benefit from the vaccine as a group, but they have close and frequent contacts with those at highest risk and are essential in the COVID-19 response. Ensuring that they remain healthy and able to work is therefore in the interest to the whole of society, allowing us all to benefit.

Promote transparency and fairness

Throughout the process of decision-making, JCVI has aspired to remain transparent. It has done this by publishing its interim advice on prioritisation (see reference 1), and by publishing the minutes of the committee’s meetings (see reference 11). This paper is a further step in ensuring transparency as to how these decisions have been made. Promoting fairness means working towards equitable access of the vaccine for everyone.

Mitigate health inequalities

Health inequalities can be structured across three dimensions: wider determinants of health, protected characteristics and social exclusion (see reference 12). The wider determinants of health (the social, economic, and environmental factors that shape mental and physical health) are ubiquitous and create a health gradient across the whole of society. Protected characteristics, such as ethnicity and sex, as outlined in The Equality Act (2010), provide an actionable framework to target those who frequently suffer worse health outcomes.

Finally, social exclusion is associated with the poorest health outcomes, putting those affected beyond the extreme end of the gradient of health inequalities. Social exclusion is the basis for the concept of ‘inclusion heath’, which typically encompasses populations such as homeless people, Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller communities, people in contact with the justice system, vulnerable migrants and sex workers, but other groups can be included.

This framework for health inequalities reminds us of our legal duty to prevent discrimination based on protected characteristics, but also of our public health commitment to improving the health of everyone across the population, with a focus on those whose health can benefit more. This means that, to reduce health inequalities, targeted action focussed on some population groups is required. The currently proposed prioritisation supports the reduction of health inequalities between age groups, by actively targeting those of older age groups and with clinical conditions above younger, healthier people.

However, it is important to keep in mind that prioritising some groups over others may have unintended consequences. PHE’s Beyond the Data report, which sought to understand the impact of COVID-19 among BAME groups early in the pandemic, reported how stakeholders expressed deep dismay, anger, loss and fear in their communities about the realities of BAME groups being harder hit by the COVID-19 pandemic than others. Some communities also reported increased experiences of stigma and discrimination as they were viewed as being more likely to be infected with the disease (see reference 13). It is paramount therefore that prioritisation and roll-out of the vaccine does not reinforce these negative stereotypes and further increase experiences of stigma and discrimination.

A similar discussion has happened with regards to occupational risk, and whether workers of some ethnic groups should be assessed differently to others, as there is a fundamental requirement to ensure people are able to work in the safest way possible. A consensus led by PHE, the Faculty of Occupational Medicine (FOM) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) concluded that “risk assessments should be applied equally and consistently across the workforce” and points out that “singling out all ethnic minority members of staff for additional risk assessments could be stigmatising and could deny them opportunities” (see reference 14).

Another key consideration for health inequalities is trust. Different communities will have a different degree of trust in the government and in the process of vaccine development and immunisation programmes, related to culture, history and other social factors. In this context of low trust among some groups, being given early access to the vaccine on the grounds of belonging to a certain community may feel like exploitation rather than inclusivity.

Unintended consequences may work to reduce health inequalities. We know that, for example, while 3.4% of the working population in England are of Black ethnic groups, this proportion is 6.1% in the NHS workforce (see reference 15). Prioritising health and social care workers will therefore indirectly provide some benefit to people of BAME groups.

Deliverability and Implementation

While scientific and ethical considerations may dominate prioritisation, the ability to operationalise these into a national immunisation programme delivered at an accelerated pace, using existing or enhanced information systems, logistics and infrastructure, is fundamental to its success. A critical component of deliverability is designing a prioritisation approach that builds public trust over time, so while it needs to have some flexibility, there should be minimal changes. The programme should be simple enough, and intuitive enough for both health care professionals and the public (including from underserved groups) to understand and buy in to.

It is important to work to proactively reduce health inequalities at implementation by identifying and addressing barriers to access and uptake of vaccination in the operational design and implementation of the programme. In England, this approach is already enshrined in the role of Screening and Immunisation Teams embedded within in Public Health Commissioning in NHS England, echoed in the PHE Immunisation Strategy vision, aims, tools and resources for implementation, and endorsed by NICE guidance (see reference 16).

Ease of identifying and contacting eligible individuals is essential for deliverability. The most comprehensive population-based health information systems are GP systems, which hold lists of patients with identifiers and contact details for the vast majority of the population. Many call and recall systems for immunisation are based on these systems. However, data on inclusion health groups or protected characteristics are variably collected. Age, sex, co-morbidities, socio-economic status (at practice level, not individual level), some behavioural factors (smoking, alcohol) and pregnancy, are comparatively well recorded and directly extractable when compared to ethnicity.

Data on inclusion health groups, such as belonging to a Gypsy, Roma or Traveller community, being homeless, or being a refugee, is almost non-existent in GP systems, although in some cases may be held in local authority systems. Incomplete or inaccurate data and the need for complex data linkages or validation steps to identify and contact eligible people increase the likelihood of increasing existing inequalities, reducing public confidence, and slowing the pace of vaccine roll out.

While prioritising certain ethnic groups has implications in terms of identifying eligible individuals, this is not the case for men as sex is almost universally recorded. However, prioritising men must be weighed against the negative impact of adding complexities to the deliverability, particularly acceptability, of the programme by essentially introducing gender bias. This may impede roll out, erode trust and undermine the higher vaccine uptake observed in the elderly that is associated with having a partner compared to being single (see reference 17). A gender-neutral programme is more likely to yield better coverage and is therefore preferable.

Monitoring of vaccine coverage of most routine immunisation programmes relies on data extracted from primary care systems. If there are specific inclusion health or vulnerable groups that are not flagged in information systems (such as rough sleepers or vulnerable migrants), this will limit our ability to identify and address inequalities in vaccine uptake.

PHE’s national immunisation equity audit (2019) illustrated this point: while the audit identified inequalities in uptake by age, geography, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion, disability and health status, travellers, migrants, prisoners, and parental factors (lone parents, large families, parental age), no assessment could be made on adults with learning disability, children or adults with physical disability, mental illness or chronic physical illness, homeless, sexual orientation and gender reassignment due to lack of systematically collected data.

To be able to monitor the impact and effectiveness, as well as safety, and detect inequalities, locally relevant data sources and intelligence therefore need to be exploited. Collaboration with public health colleagues across organisations (particularly with local authority director of public health teams), and the use of population health management approaches, can also ensure that additional datasets held by other system partners can be accessed to support the identification of specific population groups and to target specific activity to ensure improved access and more effective delivery. This would enable the development of locally sensitive approaches to access and delivery, communication, and engagement that reduce inequalities by better meeting the needs of potentially marginalised high-risk individuals and population groups.

PHE’s immunisation equity audit also highlighted the complexity of the situation: existing programmes had inequalities not just for overall coverage, but also for timing of vaccines and completion of vaccine schedules and the inequalities varied by vaccine programme, geographic locality and geographic unit of analysis, and the extent of a particular inequality in vaccination such as by ethnicity, may vary when that domain intersects with one or more other domains.

These complexities are observed in the shingles vaccination programme, which has a comparable eligible older population to the COVID-19 programme: coverage was lowest in London, decreased with increasing deprivation, and after adjusting for geography and deprivation vaccine coverage was highest for white-British, Indian and Bangladeshi groups and lowest for mixed white and black African, and black-other ethnicities (see reference 18). Uptake by sex differed by cohort: shingles vaccine uptake was higher in males for the catch-up cohort but slightly lower in males for the routine cohort (see reference 19).

Furthermore, lower vaccine coverage in high risk groups does not always equate to low impact of the vaccine programme. This was borne out in a study in Merseyside looking at rotavirus vaccine uptake and acute gastroenteritis hospitalisations; vaccine impact (that is reduction in hospitalisation rates) was greatest among the most deprived populations, despite lower vaccine uptake, because the baseline absolute risk was so high (see reference 20). In the context of a COVID-19 vaccine programme, even if vaccine uptake falls short in some high-risk groups, health benefits may still be realised in terms of disease burden reduction.

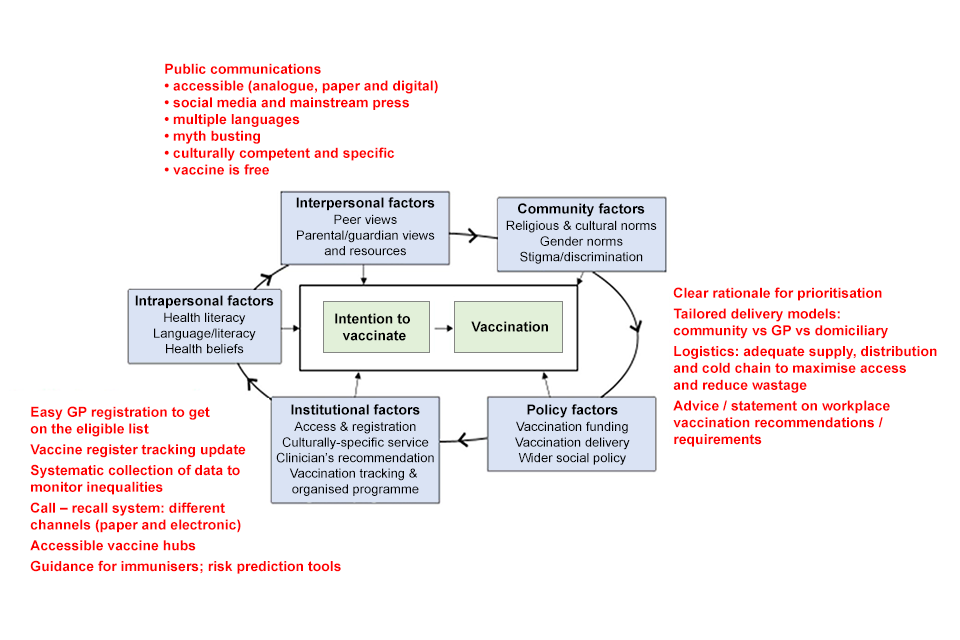

A socioecological model of factors influencing inequalities in vaccination uptake has been developed (figure 1) based on the audit’s findings. This model provides a framework for actions to mitigate inequalities which can be applied to the COVID-19 immunisation programme. For example, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors such as vaccine beliefs around safety should be addressed through a communications strategy that is culturally competent and specific, with resources in multiple languages, and using several media (to avoid digital exclusion). To ensure equitable access for groups where mobility may be a challenge (for example elderly and those with physical disabilities), who have poor access to traditional health services, or are essential health and care staff, a policy of multiple models of vaccine delivery (such as domiciliary, community hubs, GP, secondary care and outreach) should be considered. Programmes targeting working-age adults, for example for influenza, are usually easier to deliver through occupational settings (such as NHS trusts) and achieve higher vaccine uptake, including in BAME staff through occupational health risk assessments; this delivery model also allows for large volume of stock to be held at vaccination sites with high footfall which can reduce wastage if multi-dose vials are used.

A collaborative approach to delivery of immunisation programmes, with system partners, is a fundamental part of the role of Screening and Immunisation Teams embedded within in Public Health Commissioning in NHS England. These teams in England (and their equivalent in devolved administrations) have knowledge of their local populations and are experienced in implementing both targeted and universal population immunisation programmes at pace, and in applying a variety of tools and actions to address issues related to equity and access.

For example, the South West flu team have worked with lower performing GP practices in deprived areas on targeted behavioural change messages and used postcard drops, engaged with networks for migrants and people with learning disabilities, developed toolkits to increase vaccine uptake with learning disability nurses, and worked with GPs, local authorities and CCGs to provide vaccination for the traveller community at traveller sites and commission flexible models of vaccine delivery for homeless people. The skills, knowledge and experience of Screening and Immunisation Teams should be utilised to ensure that mobilisation of the COVID-19 vaccination programme is achieved, not only at pace but in a way that minimises the impact of any potential inequalities arising from a prioritisation approach.

Summary

This paper sets out some considerations regarding the currently proposed prioritisation of COVID-19 vaccine which is necessary due to initial limited supply of vaccine.

The conceptual framework adopted is one based on consideration of scientific evidence, ethics and deliverability, with a focus on the ethical principles of maximising benefit and minimising harm, promoting transparency and fairness, and mitigating inequalities in health.

While age has the absolute highest risk of poor COVID-19 outcomes, many factors are associated with an increased relative risk (such as belonging to a BAME group and being male). These are mediated by a complex web of factors which are not straightforward to disentangle and can be potentially misleading, and if misinterpreted when translated to policy, can be damaging to populations and widen health inequalities.

The current prioritisation achieves an acceptable balance between scientific evidence, ethics and deliverability, based on clinical risk as determined by age, clinical conditions, and health and social care worker status (thus providing NHS resilience). While prioritisation alone cannot address all inequalities in health that are rooted in social determinants, planning and implementation should as a minimum not worsen health inequalities, and present a unique opportunity to mitigate them.

While prioritisation is set nationally, the knowledge, experience, system leadership and collaborative approach with local partners of Screening and Immunisation Teams embedded within in Public Health Commissioning in NHS England (and their equivalent teams in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) should be utilised to improve vaccine uptake and reduce inequalities in the implementation of the COVID-19 immunisation programme.

Table 1: summary of population groups and considerations for prioritisation

| Population group | Scientific evidence | Ethics | Deliverability and implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Older age groups | Highest absolute risk of morbidity and mortality | Maximises benefit and reduces health inequalities | Age is almost universally recorded on NHS records, so easy to identify individuals; flexible delivery model to reduce inequalities in vaccine uptake |

| People with high-risk clinical conditions | Elevated relative risk; comorbidities increase with age; mediated/driven by other factors | Maximises benefit and reduces health inequalities | High risk clinical conditions are well recorded on NHS records, so individuals are easy to identify; flexible delivery model to reduce inequalities in uptake |

| Health and social care workers | Elevated relative risk – mediated/driven by other factors not just occupation; vaccination of staff protects vulnerable patients | Contributes to individual benefit and population benefits: protect patients and ensure NHS and adult social care resilience | Health and social care workers can be identified through occupational health structures; established delivery model in occupational settings |

| Men | Elevated relative risk – mediated/driven by other factors, not just biological or genetic | Some benefit achieved by vaccinating older age groups and those with high risk clinical conditions | Sex is almost universally recorded on NHS records, so men would be easy to identify |

| Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups | Elevated relative risk – mediated/driven by other factors, not just biological or genetic | Risks further increasing stigma Some benefit achieved by vaccinating health and social care workers | Ethnicity recording on NHS electronic systems is poor quality, so individuals would be difficult to identify; communications strategy and flexible delivery model to reduce inequalities in vaccine uptake |

Figure 1: socioecological model of factors influencing inequality in vaccination (from immunisation audit) and potential actions to mitigate inequalities in planning and implementation (red)

The figure shows the factors that influence the process between the intention to vaccinate and actual vaccination.

The factors include:

- interpersonal factors such as peer views, parental and guardian views, and resources

- community factors such as religious and cultural norms, gender norms, and stigma and discrimination

- policy factors such as vaccination funding, vaccination delivery and wider social policy

- industrial factors such as access and registration, culturally-specific service, clinician’s recommendation, and vaccination tracking and organised programme

- intrapersonal factors such as health literacy, language and literacy, and health beliefs

Mitigating factors include:

- public communications such as:

- accessible (analogue, paper and digital)

- social media and mainstream press

- multiple languages

- myth-busting

- culturally competent and specific

- vaccine is free

- clear rationale for prioritisation

- tailored delivery models: community versus DP versus domiciliary

- logistics: adequate supply, distribution and cold chain to maximise access and reduce wastage

- advice and statements on workplace vaccination recommendations and requirements

- easy GP registration to get on the eligible list

- vaccine register tracking update

- systematic collection of data to monitor inequalities

- a call recall system using different channels (paper and electronic)

- accessible vaccine hubs

- guidance for immunisers and risk prediction tools

Authors: Ines Campos-Matos (PHE) and Sema Mandal (PHE)

Contributors: James Wilson (UCL), Julie Yates (PHE), Gayatri Amirthalingam (PHE), Mary Ramsay (PHE), Andrew Earnshaw (PHE)

5 November 2020; revised 18 November 2020

References

- Priority groups for coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination: advice from the JCVI, 25 September 2020

- Chamberland ME. Ethical Principles for Phased Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccines, ACIP meeting, 20 October 2020

- Ward H, Atchison CJ, et al. Antibody prevalence for SARS-CoV-2 in England following first peak of the pandemic: REACT2 study in 100,000 adults

- Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7821):430-436.

- Clift, Ash K., et al. Living risk prediction algorithm (QCOVID) for risk of hospital admission and mortality from coronavirus 19 in adults: national derivation and validation cohort study. BMJ 371 (2020).

- PHE. 2020. COVID-19: review of disparities in risks and outcomes

- OPENSafely. Absolute risks by age, comorbidity and ethnicity. (Unpublished OpenSafely Collaboration paper for JCVI)

- Bhopal SS & Bhopal R. Sex differential in COVID-19 mortality varies markedly by age. The Lancet, Volume 396, Issue 10250, 532 – 533

- Krieger, Nancy et al. Excess mortality in men and women in Massachusetts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, Volume 395, Issue 10240, 1829

- SAGE Ethnicity sub group. Drivers of the higher COVID-19 incidence, morbidity and mortality among minority ethnic groups, 23 September 2020

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation

- Campos-Matos, Ines et al. From health for all to leaving no-one behind: public health agencies, inclusion health, and health inequalities. The Lancet Public Health, Volume 4, Issue 12, e601-e603

- PHE 2020. Beyond the data: Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups

- Race Disparities Unit, Cabinet Office. Quarterly report on progress to address COVID-19 health inequalities, October 2020

- GOV.UK NHS workforce

- NICE. Public Health Guidance 21 Immunisations: reducing differences in uptake in under 19s. 2017

- Schmitz H and Wubker A. What determines influenza vaccine take up in Elderly Europeans? Health Econ 20:1281-1297 2011

- Ward C, Byrne L, White JM, Amirthalingam G, Tiley K, Edelstein M. Sociodemographic predictors of variation in coverage of the national shingles vaccination programme in England, 2014/15. Vaccine. 2017;35(18):2372-8. pmid:28363324

- Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2017 to 2018: evaluation report

- Hungerford, D., Vivancos, R., Read, J.M. et al. Rotavirus vaccine impact and socioeconomic deprivation: an interrupted time-series analysis of gastrointestinal disease outcomes across primary and secondary care in the UK. BMC Med 16, 10 (2018)